*Local Learning Series written by Bonnie Bradt member of UCCE Master Gardeners of Nevada County and lives in Grass Valley, CA.

Least Toxic Methods of Insect Control

Let’s face it, fellow gardeners, historically, the concept of “pest control” consisted of dusting or spraying, with the goal of eliminating every pest in the landscape. As an entomology student at UC Davis, in the early 1970’s, I was required to memorize the toxicities of long lists of pesticides and was taught how to use them.

Fortunately for all of us, the more sensible, moderate approach known as IPM or Integrated Pest Management has, today, moved into the forefront of pest control practices. The goal of IPM is to make use of a collection of the least toxic methods available to reduce pest populations to tolerable levels. As we all know, however, “tolerable” is in the eye of the beholder.

So we must all open our eyes to a new way of seeing our gardens. First, we need to learn a degree of acceptance of pest damage. Our produce is not headed for the local commercial market and does not have to maintain blemish-free perfection.

Also, the sight of an aphid (or two) on our rosebushes need not trigger the appearance of the pesticide spray bottle. Look upon those aphids as food for the up-and-coming populations of ladybeetles and lacewings.

Concern has grown, among the gardening public over the use and “misuse” of pesticides. This has led, over time, to a demand for information on less toxic alternatives to the standard shelf of chemical controls formerly lined up in the garden shed. Following is a necessarily brief discussion of the three main alternatives to chemical control of insect pests in the home garden. For those of you who are new to IPM, just try to think as you read, how you could introduce even a few of them into your daily garden routine.

CULTURAL CONTROLS

Certain cultural control practices can minimize garden pest damage. A thorough discussion is available in the California Master Gardener Handbook. Each of the following methods involves ways to grow plants that are healthier and resistant to damage by insect pests.

These include but are not limited to:

- Use of resistant varieties

- Digging, tilling and cultivating

- Crop Rotation

- Proper use of fertilizer and water

- Adjustment of planting or harvest time

- Sanitary practices

- Companion planting

Genetically resistant varieties of plants may be better able to resist damage or repel pest insects. They may be less tasty to the pest. Or they may be able to support larger pest populations without appreciable damage.

Cultivation and digging of garden soil can expose soil pests to air and sun or birds and other predators, or bury them deeply enough to kill them, all of which can help control pest numbers.

Crop rotation can effectively move target host plants away from their pests, especially if the pest has a short migration range.

Do not plant members of the same crop family in the same location for successive years or the pests will have no trouble finding their preferred food sources without even moving.

Fertilizers, organic matter and water, applied properly, will help you grow healthy plants which are always more resistant to pest damage than weak and unhealthy ones.

Planting earlier in the season, with the help of hot caps or row covers, etc., can help protect plants from pests during the fragile seedling stage. Delaying the planting of certain seeds until heat allows for quick germination can reduce seed damage by maggots. Adjusting your planting dates to the appearance of pest populations is possible only if you are familiar with the biology of the pest in question.

Keeping the soil under and around your plants and trees cleaned up, especially at season’s end, can eliminate food and shelter for pests that would otherwise trouble you the next year after overwintering in your crop residue.

MECHANICAL CONTROLS

This variety of insect control utilizes such things as the following, to safely reduce pest numbers:

- Physical/preventive barriers

- Washing

- Traps

- Hand picking

Barriers, though easy to use, vary in their effectiveness. Try them in your own garden to see what works best. Paper collars can reduce cutworm damage to seedlings. Cheesecloth screens can prevent egg-laying by some insects. Mesh covers over fruit trees/berry bushes can keep out birds until the harvest is ready for you to get there first (I know that one works!). Sticky barriers can prevent ants from traveling up your trees to herd, harvest and protect aphids and their honeydew.

Washing plant leaves with a sturdy stream of water can help control leaf-feeding insects. But you must keep at it. Wash the plant on successive days to keep the pests under control. And save this method for hardier plants so the water won’t do more damage than good.

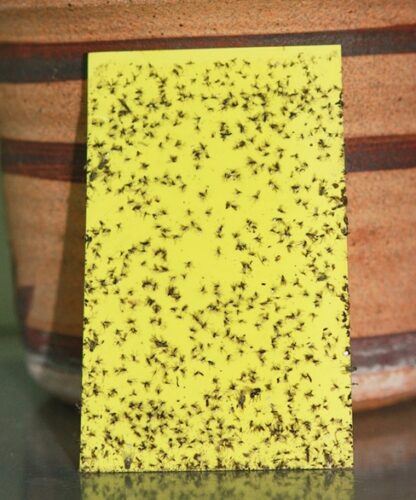

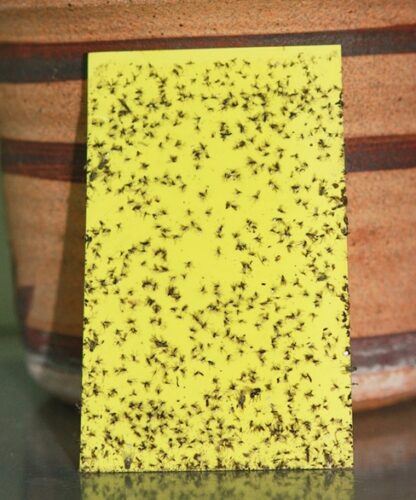

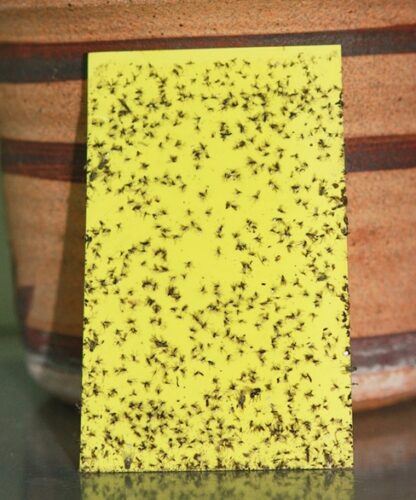

Traps can be used either to physically catch insects or to confuse them. The best traps have pest specificity and low general toxicity. Something as simple as a dish set into the soil and filled with stale beer can attract and kill slugs and snails (just keep it away from the dog!). Conversely, a well-planned, sophisticated pheromone trap system can be hung in target trees as part of an intricate codling moth control program. Earwigs can be “trapped” in a tightly rolled tube of newspaper where they will take shelter. “Sticky” traps, charged with pheromone lures can be placed in your pantry to catch and kill the moths whose larvae infest grain products.

Last but not least, mechanical control by hand picking garden culprits is actually an effective method. It’s especially helpful if you start early in the season, before the problem escalates into something overwhelming.

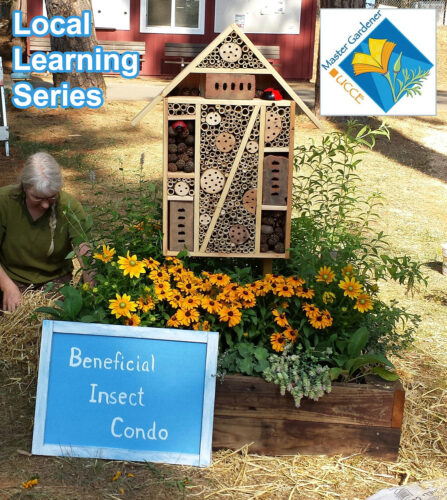

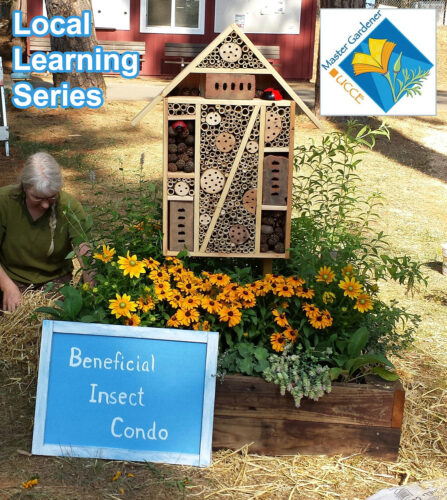

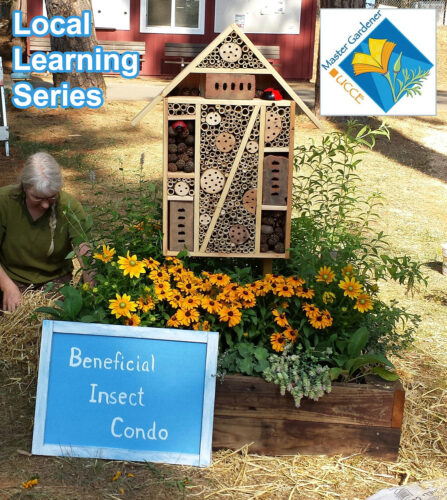

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS

The broad definition of biological control given in the Master Gardener Handbook is a good one: “…any activity of one species that reduces the adverse effect of another (species).” This particular non-toxic method of insect control is the one nearest and dearest to my heart, but is the least understood of all methods. It is a seductive picture for a gardener to imagine purchasing and releasing hordes of insect predators who will spread out over their garden, ravaging the pest populations as they go.

There are problems with this lovely but impractical idea. There is some variation in quality of the agents available for purchase. Viability is better for some than for others based on the supplier and on the handling of the beneficials by the retailer who sells them and the consumer (you) who buys them.

There is also a lack of continuity of instructions for release into the garden. Overloading your garden with released predators, if the pest populations are low, is either a death sentence for the predators or it means they will move into your neighbor’s yard, looking for food. Certainly the release of ladybeetles, collected during their dormancy, is asking for problems. These critters will wake up from their dormant state with a strong instinct to fly away…to the neighbor’s yard again, or maybe to the next town. Finally, the release of praying mantids, in quantity, is of questionable value in that, while they are certainly predators of insects, they prey on beneficials as well as pests. I’ll suggest a more practical way to elevate the populations of beneficials in your garden. Encourage the naturally occurring “good guys” to move in and stay.

They’re there, all around you.

But such practices as broad-spectrum pesticide use or denuding of the landscape by herbicides and layers of gravel will discourage the activity and reduce the populations of naturally occurring predators.

Make your garden a place that beneficials will find appealing. Give them what they need. They need food, shelter and safety from death by poison. UC ANR publication #3332 below, gives a list (p 25) of flowering plants you can grow to encourage adult beneficials who need nectar and pollen to reproduce. Remember, also, SOME low level of pest population must be tolerated to provide food for the larval predators. If it’s hard to look at those aphids on your roses or veggies just think of this – if you don’t provide food for the beneficials they won’t inhabit your garden…and you’ll inherit their work.

—

California Master Gardener Handbook, 2002, Dennis R. Pittenger, Ed., UC ANR Publication #3382

Pests of the Garden and Small Farm: A Grower’s Guide to Using Less Pesticide, 1998, Mary Louise Flint, UC ANR Publication #3332

—

Bonnie Bradt received a Master Degree in entomology from UC Davis in the early 1970’s and has worked in private and University research laboratories until her retirement from UC Davis in 2011. Bonnie has lived in Grass Valley for 20 years and has been in the UCCE Master Gardeners of Nevada County for over 15 years. She has taught many classes to local home gardeners on the subject of entomology in the garden and many other topics.

For more information about UCCE Master Gardeners of Nevada County visit www.ncmg.ucanr.org

Need some help in your garden? Call the MASTER GARDENER HOTLINE OFFICE: 530-273-0919

255 South Auburn Street, Grass Valley – in the Veterans Memorial Building

Their Hotline Office is staffed Tuesdays & Thursdays from 9:00am to Noon. During this time, you are welcome to call in or come into the office and bring us a sample of the problem. If the office is closed, you can leave a message and a Master Gardener will return your call on the following Tuesday or Thursday.

If you would like to submit a question electronically, please click on the link below and fill out the form. You may also attach up to three (3) digital photos pertaining to the problem.